For many new entrants to the solar industry, coming up with the best solar design for a homeowner is a daunting process. You have to take into account environmental conditions like the site location, available roof area, and shading considerations. You also have to make sure you have the right number and combination of modules and inverters to hit your energy target. Try doing all of this live at the kitchen table in front of a homeowner and it can be a nightmare.

Historically, every PV system has had to be designed manually. But the multitude of factors to be considered makes this design problem difficult and time-consuming for humans to solve. For instance, a proposed design might include an inverter that is too small to handle the current of an array or panels might be situated in a way that violates fire codes or setback requirements.

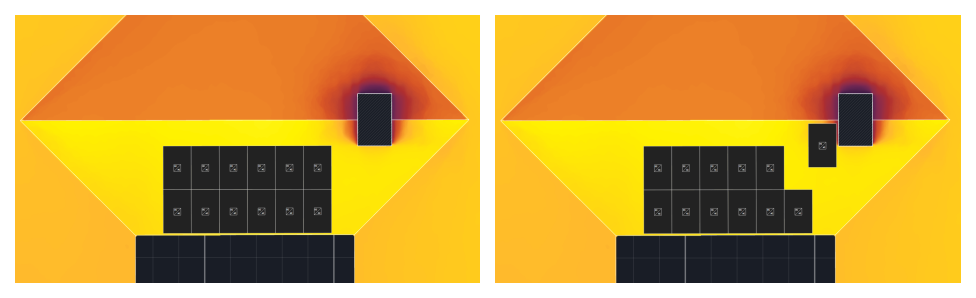

Even in the absence of violations like these, the proposed design may not be the best design. For example, designers might not consider that just by changing their stringing configuration, they could substantially boost the energy production of their array (our analysis of a shaded site found improvements of over 17% annually).

But what if this fundamental question in solar design—“What is the best system design to meet a customer’s goals?”—could be answered by a computer?

Not only could you ensure consistently optimal designs for customers, but hours of design time and associated costs could be saved. Beyond the benefits for individual designers and companies, this kind of automated design could dramatically reduce the cost of solar, making sustainable solar energy available to more people.

Solving these pressing needs in the solar industry was at the forefront of our minds, when Aurora set about developing the “AutoDesigner”—to make it possible to find the best solar design with just the click of a button. Nothing like this had ever been done before, however, and the scope of the challenge was vast.

Given all the design variables, the number of possible designs for a site is often upwards of one quadrillion. To put this into perspective, if a human could evaluate a design per second, it would take them over four hundred thousand lifetimes to get through them all!

In today’s article, we dive into how Aurora solved this challenge, and explain the inner workings of how the AutoDesigner finds the optimal solar system for a particular site.

The Aurora AutoDesigner Team

With such a difficult undertaking ahead of us, we needed to get the right people and resources in on the process. In 2014, Aurora was honored to receive a Sunshot Grant for this undertaking. Over the course of two years, the Aurora team worked with top scientists in the fields of optimization and computational mathematics to develop the algorithms and infrastructure that drive the AutoDesigner.

Consulting Scientist Dr. Madeleine Udell is Assistant Professor of Operations Research and Information Engineering and Richard and Sybil Smith Sesquicentennial Fellow at Cornell University. She completed her Ph.D. at Stanford University in Computational & Mathematical Engineering in 2015, and a one-year postdoctoral fellowship at Caltech in the Center for the Mathematics of Information.

Quantitative Engineer Mitchell Dawson joined Aurora in 2016. He completed his B.S. in Computer Science in June 2017 with an emphasis in Artificial Intelligence, and is currently working towards his M.S. in the same field.

Defining the Challenge of Automated Solar Design

To create a computer program capable of finding the optimal solar design, we had to articulate the design question in mathematical terms. Specifically, we had to formulate equations that characterize the mathematical relationships between various aspects of the design question. We started by defining the pieces of information that must be provided and what variables the equation would solve for.

Required Inputs

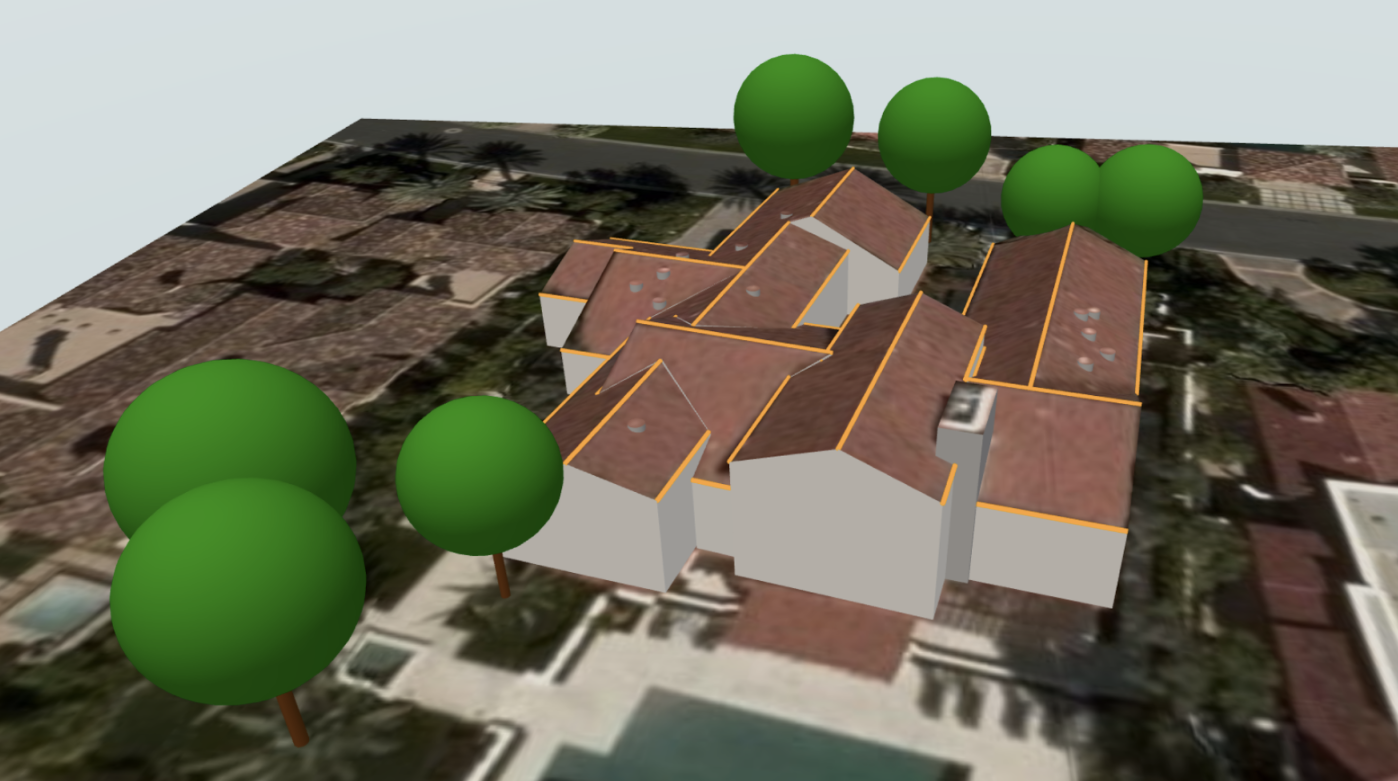

We had to start by considering what information must be known to create the optimal design. The key inputs include: an accurate 3D Site Model, the available hardware components, weather data, utility rates, and especially the customer’s objectives for the design.

An accurate 3D Site Model—including trees and obstructions which dramatically impact the shading on some roof faces—provides the starting point for finding an optimal design for a specific site. This determines the spatial limitations on where panels can be placed, and how much energy they will produce.

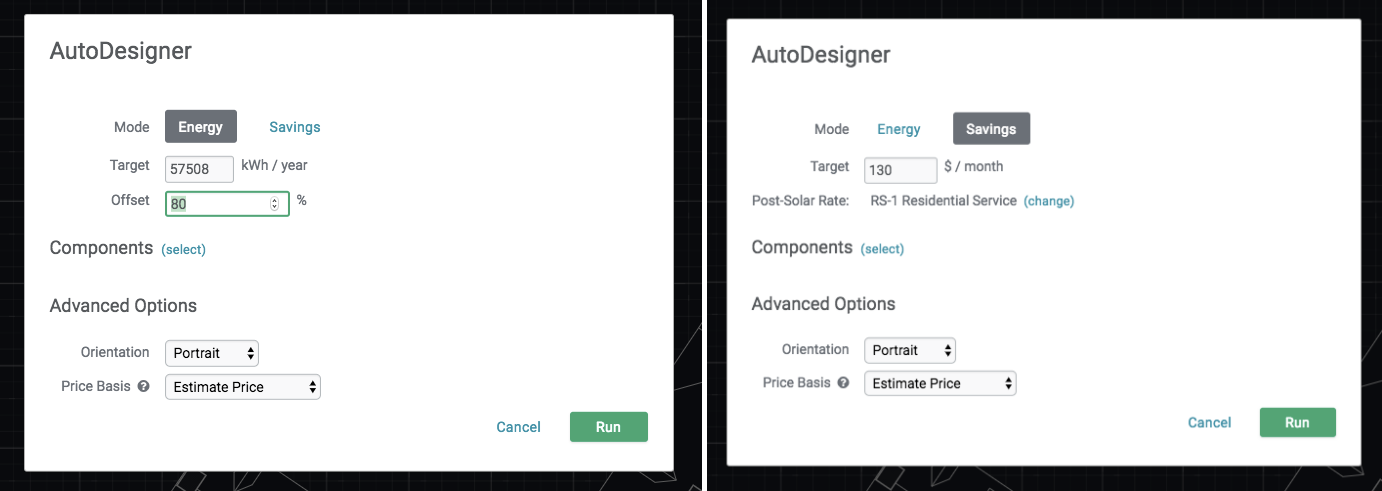

It is also essential to provide the AutoDesigner with the customer’s objectives for the solar system. For instance, a customer may want to offset a specific amount of their energy consumption, or they may want to maximize bill savings. In the AutoDesigner system, Design Targets can be entered as either a desired percentage of the customer’s energy consumption they would like to offset or a target amount of bill savings.

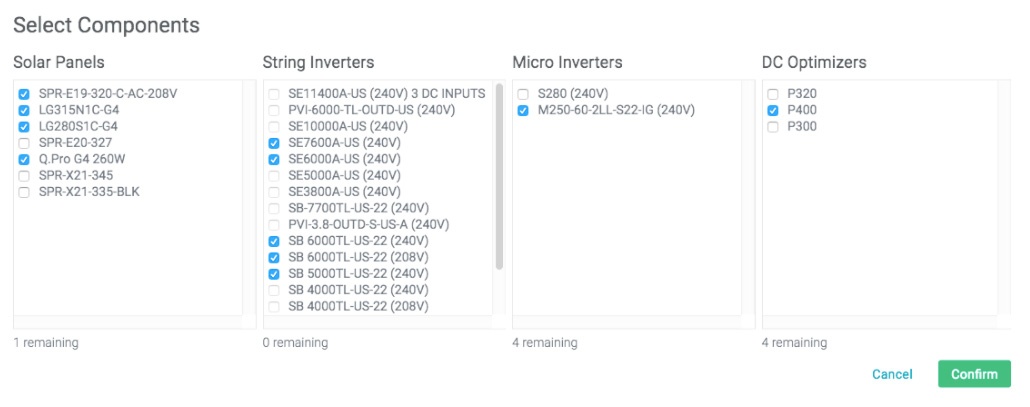

Other vital pieces of information are the components the AutoDesigner can choose from, local weather data for the site, and the relevant utility rates. Once available components—including panels, string inverters, microinverters, and DC optimizers—are specified, the AutoDesigner will evaluate designs containing some or all of the selected components to find the best ones for the particular site. Local weather data, which will impact expected energy production, must also be provided. The AutoDesigner obtains this data from local weather stations to simulate the energy production of each design on an hour-by-hour basis.

Finally, if a customer’s objective is a bill savings target, we must provide the pre- and post-solar utility rates. Using Aurora’s financial analysis capabilities, the AutoDesigner performs a full financial analysis for each candidate design to find the approach that maximizes savings. The financial simulation is compatible with diverse utility rate structures including tiered rates, time of use (TOU) rates, and even California’s NEM 2.0 rate.

What Variables Does the AutoDesigner Solve for?

The primary variables that the AutoDesigner solves for are panel locations and inverter configurations, though other elements are ultimately considered to arrive at an optimal design.

Given the 3D site model, the AutoDesigner assesses all potential placements of solar panels, with some limitations on how the arrays can be arranged. Modules cannot overlap, nor should they be spaced out randomly across the roof face. Additionally, designs with rectangular arrays, that are located in high energy locations, are preferred.

The second key variable that the AutoDesigner solves for is inverter configuration, or the way that panels are connected to inverters. The AutoDesigner considers how many of each inverter type are needed, as well as the engineering specifications that dictate how they may be connected. In the case of microinverters, this is a relatively simple process; each panel is assigned a unique inverter. However, for string inverter and DC optimizer designs, panels must be strung to an inverter. String lengths must be compliant with the latest NEC rules and obey the inverter’s voltage, current, and power limits.

Additionally, the performance implications of different inverter configurations must be considered. For example, in the case of string inverters, if a single panel is shaded then the energy output of the entire string of panels will be reduced. Finally, panels should be strung in such a way that reduces wire cost and installation time for the design.

How the AutoDesigner Arrives at the Optimal Design

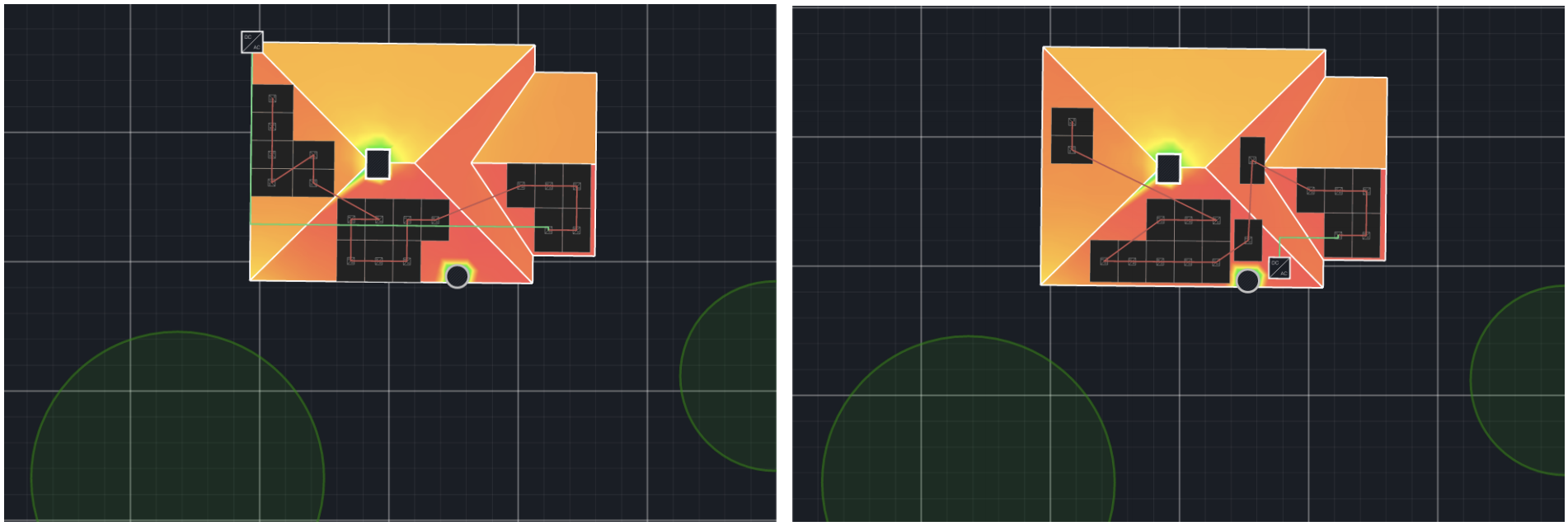

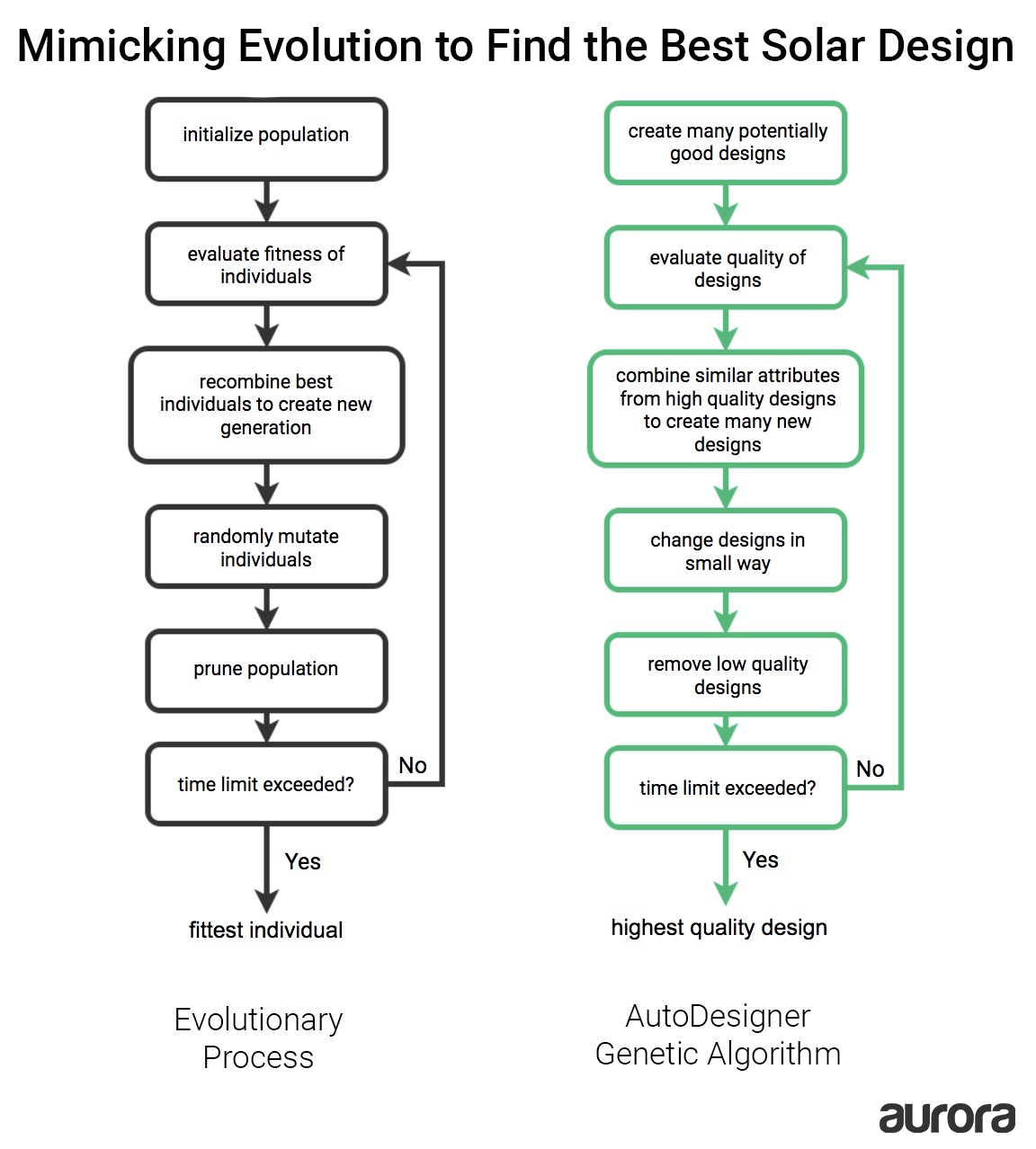

The AutoDesigner was developed to work via a two-part process. First, the design problem is solved mathematically to arrive at a preliminary design for the site. Then, a “genetic algorithm”—which mimics the evolutionary process in nature—iterates through potential combinations, to arrive at an optimal design.

The Optimization Problem

To start with, the AutoDesigner uses a mathematical optimization algorithm (based on linear programming) to solve the problem (i.e., panel locations and inverter configurations) exactly.

Another way of asking “what is the optimal design for a particular site?” is:

“What design will minimize cost, a) without violating electrical constraints (e.g. string length and voltage/current/power requirements of inverters) and b) while meeting the customer’s design targets (producing the desired amount of energy or bill savings)?”

This statement provides the basis for the optimization algorithm.

If the customer’s design target is to offset a set amount of their energy consumption, potential panel locations are evaluated based on the amount of energy a particular location would produce. Alternatively, if the customer’s design target is reducing their bills by a set amount, this evaluation is based on how much a panel in that location would contribute to overall bill savings.

This approach reaches a solution in a purely mathematical sense, without taking into account aesthetics or other design subtleties. This provides a starting point for evaluating potential designs.

Simulating Evolution to Reach the Optimal Design

Next, a genetic algorithm, which simulates the evolutionary process, is used to iterate through thousands of potentially desirable design variations and move towards the most “fit” variations.

Given the complexity of the problem, we didn’t want to reinvent the wheel. Instead, the Aurora team looked to nature for a solution. A genetic algorithm that models the evolutionary process of natural selection provides a powerful way of reaching an optimal design. In this process, a group of solar designs is the equivalent of a population of individuals in nature.

Each design has certain characteristics that make it distinct, just like any individual. The genetic algorithm programmatically simulates many generations, where designs (i.e., “individuals”) pair off and combine their traits to produce new designs, or “offspring.” Algorithms like this one rely on powerful computers to simulate the recombination and mutation of thousands of individuals in a fast way.

To initiate the process, AutoDesigner creates a diverse set of potentially good designs to make up its population. It then combines these designs to create diverse “offspring” and evaluates the fitness of each resulting design (scoring them based on a variety of factors including: energy production, bill savings, aesthetics, hardware costs, and installation costs). Unfit designs are eliminated at each “generation” and the process continues until an optimal design is reached.

What Does Automatic Design Mean for the Solar Industry?

Aurora’s consulting scientist, Dr. Madeleine Udell, states that “the AutoDesigner solves a major problem in the residential solar industry: automated design of cost-effective, efficient rooftop photovoltaic PV installations.” The AutoDesigner is a powerful tool for seasoned solar designers as well as those new to the industry, whether you are trying to minimize shade losses, or impress a prospective client with a customized design to meet their goals. In addition to saving for individual designers and solar companies time and money, the AutoDesigner can help lower the soft costs of solar, making this clean energy source cheaper and more accessible.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory analyzed Aurora’s AutoDesigner to see how its proposed designs compared to those designed by human designers—in terms of project cost and meeting energy production or bill savings targets. In more than 70% of tests, the AutoDesigner’s designs performed better than those produced by the designer.

While there is still work to be done, the AutoDesigner provides a strong foundation for allowing any solar professional to create faster, cheaper, and more efficient installations, all with just the click of a button.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Oliver Toole and Mitchell Dawson for their advice on the development of this article and providing substantial content.

Notes:

-

Figure 1 depicts a simplified design challenge for a house that did not require fire code setbacks. For a detailed overview of NREL’s analysis and Aurora’s AutoDesigner, see “Optimal Design of Efficient Rooftop Photovoltaic Arrays.” ↩